Medical History, Mary Shelley, & Frankenstein

Surgery, Dissection, & Bodysnatching

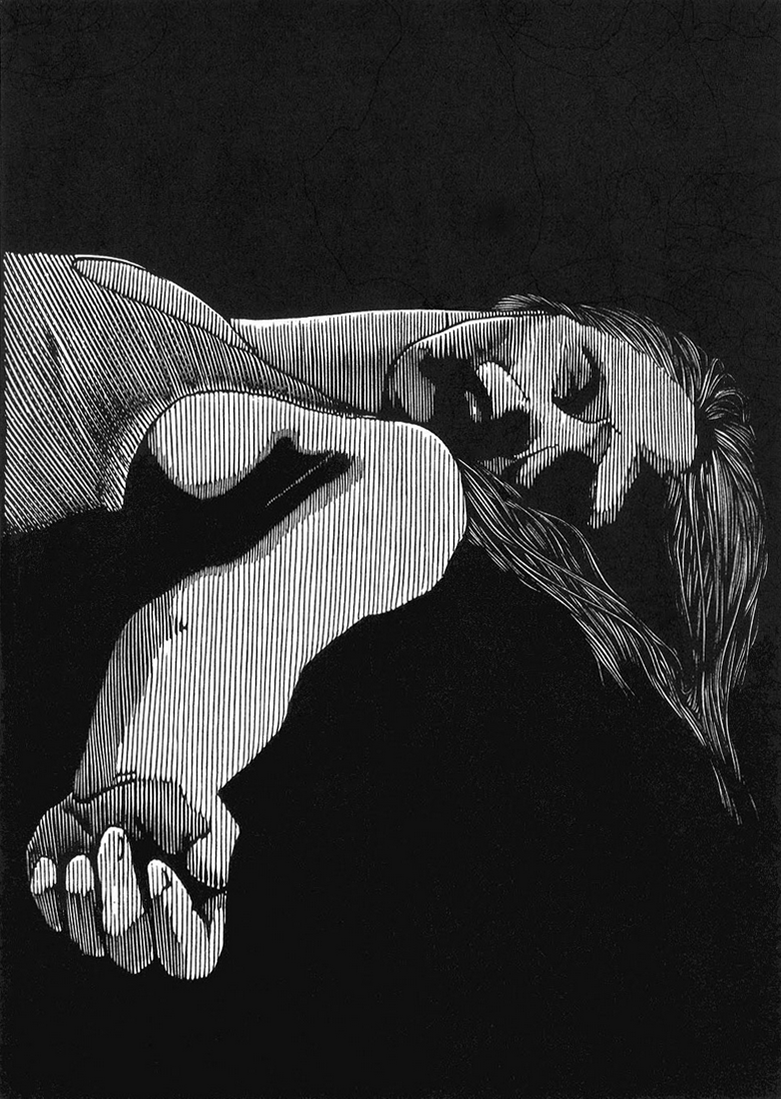

"It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs."

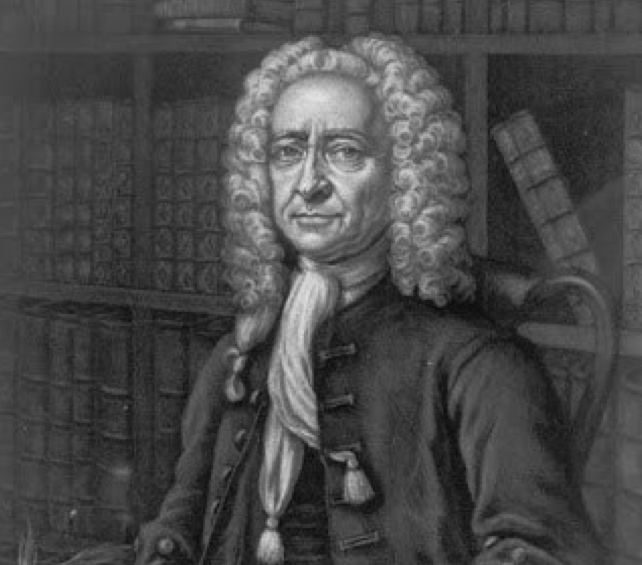

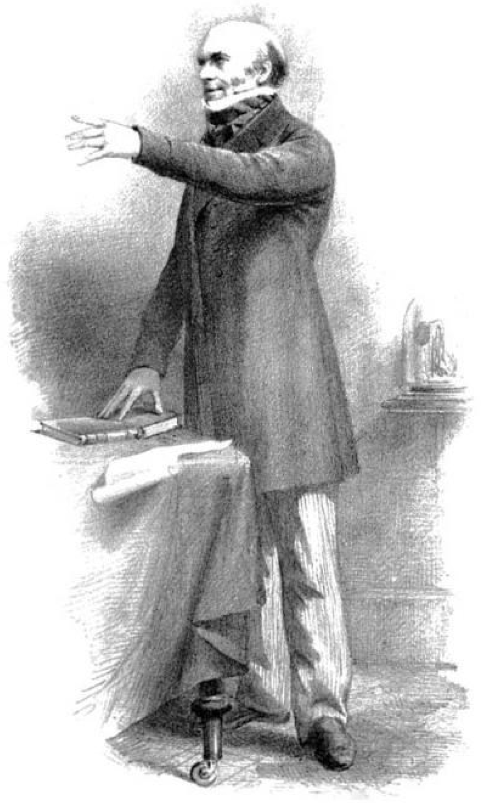

Daniel Turner (1667-1740), The art of surgery (1736)

Daniel Turner, recipient of the first medical diploma granted by an American school (Yale), was born in London. There he spent an extremely active professional life, practicing the art and writing on diverse subjects. He also wrote the first dermatological text in English in 1714.

Sir Charles Bell (1774-1842), A system of dissections, explaining the anatomy of the human body, the manner of displaying the parts, and varieties in disease (1799)

Among Bell’s many contributions to medical science may be included his role in establishing the motor and sensory pathways of the spinal nerves. All his discoveries were, in his own phrase, "deductions from anatomy." All the drawings for the illustrations in his books were made by him, and they stand unrivaled for their facility, elegance, and accuracy. This work represented Bell's first independent publication as an author and appeared when he was twenty-four years old. It covers dissection of the abdomen, thorax, pelvis, thigh, and leg. Volume II was issued in two parts in 1801 and 1803. It covers dissection of the arm, neck, face, and nerves of the viscera, brain, and eye.

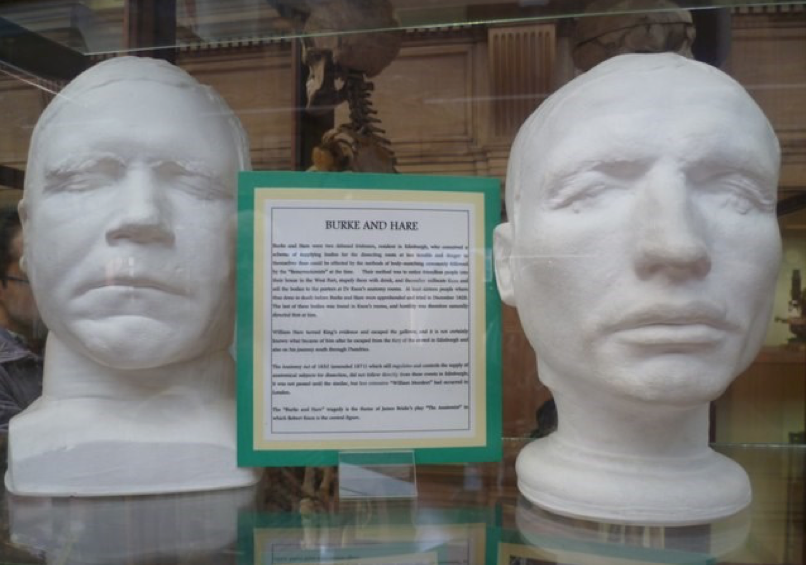

The Burke & Hare Murders—Edinburgh (1828)

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of 16 murders committed by William Burke and William Hare in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1828. The pair would befriend their victims, murder them (usually by suffocation) and then sell the bodies to Doctor Robert Knox at the Royal College of Surgeons for use as dissection specimens.

After Burke and Hare were caught, Hare gave evidence against Burke and was not executed. Burke was hung in January 1829 and his body was dissected at the Royal College. His skeleton is still in the Anatomical Museum of the Edinburgh Medical School.

This case was important because it raised public awareness of the need for legally-obtained medical specimens. In 1832, the Anatomy Act opened up the law to allow the dissection of unclaimed bodies, instead of only those of executed murderers.

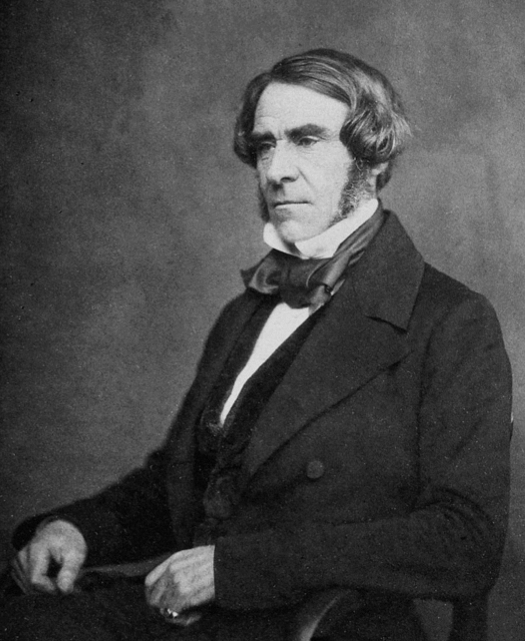

Sir Robert Christison (1797-1882), A treatise on poisons (1845)

One of the leading toxicologists of the nineteenth century, Christison was well known for his testimony in the trial of Burke and Hare, the notorious resurrection men, and was instrumental in their conviction for murder.

In toxicology and pharmacology he performed major research on arsenic poisoning, the effects of oxalic acid, the action of water on lead, and he investigated the properties and physiological effects of Calabar beans, coca leaves, opium, and wine. The cited work, first published at Edinburgh in 1829, became the authoritative work on poisons for many years.

Robert Knox (1793-1862), Man, his structure and physiology: popularly explained and demonstrated (1858)

Knox was an anatomist and lecturer at Edinburgh University who is believed to have purchased bodies for dissection from the infamous murderers William Burke and William Hare. When the crimes came to light, Knox was inevitably implicated, and he was savagely attacked in the literature of the day. Although exonerated by Burke, Knox was nevertheless accused of acting incautiously and of failing to ensure that his assistants properly vetted their suppliers, and thus the episode was to haunt and tarnish the rest of his career. He did, however, manage to publish a few books later in life. This is the second edition of Knox’s attractively illustrated and popular introduction to anatomy and physiology.

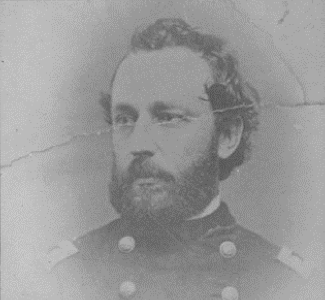

Body Snatching in Iowa City (1870)

Dr. Henry Boucher, c. 1863. James Henry Boucher, head of Anatomy and Assistant Surgeon, was part of the first medical faculty at the State University of Iowa. He left during his first year due to a grave robbing scandal.

Mary Herrick ( - 1870), venerable and venerated, a Mother dearly beloved by sons and daughters.

Reported facts: Mary Herrick’s body was removed from her fresh grave and partially dissected by medical students. When discovery was imminent her body was hidden in a haystack, then delivered to undertakers with the face dissected.

"Scarcely a greater cruelty could be inflicted upon any small town than to establish therein a medical college. To do so, is to virtually subject its inhabitants to the constant dread of having their dead transferred from their coffins to the dissecting table."

"If we cannot entomb our friends and rest perfectly assured that they will rest undisturbed, better annihilate the Medical Department and raze the building to the ground."

James Blake Bailey, The diary of a resurrectionist, 1811-1812 (1896)

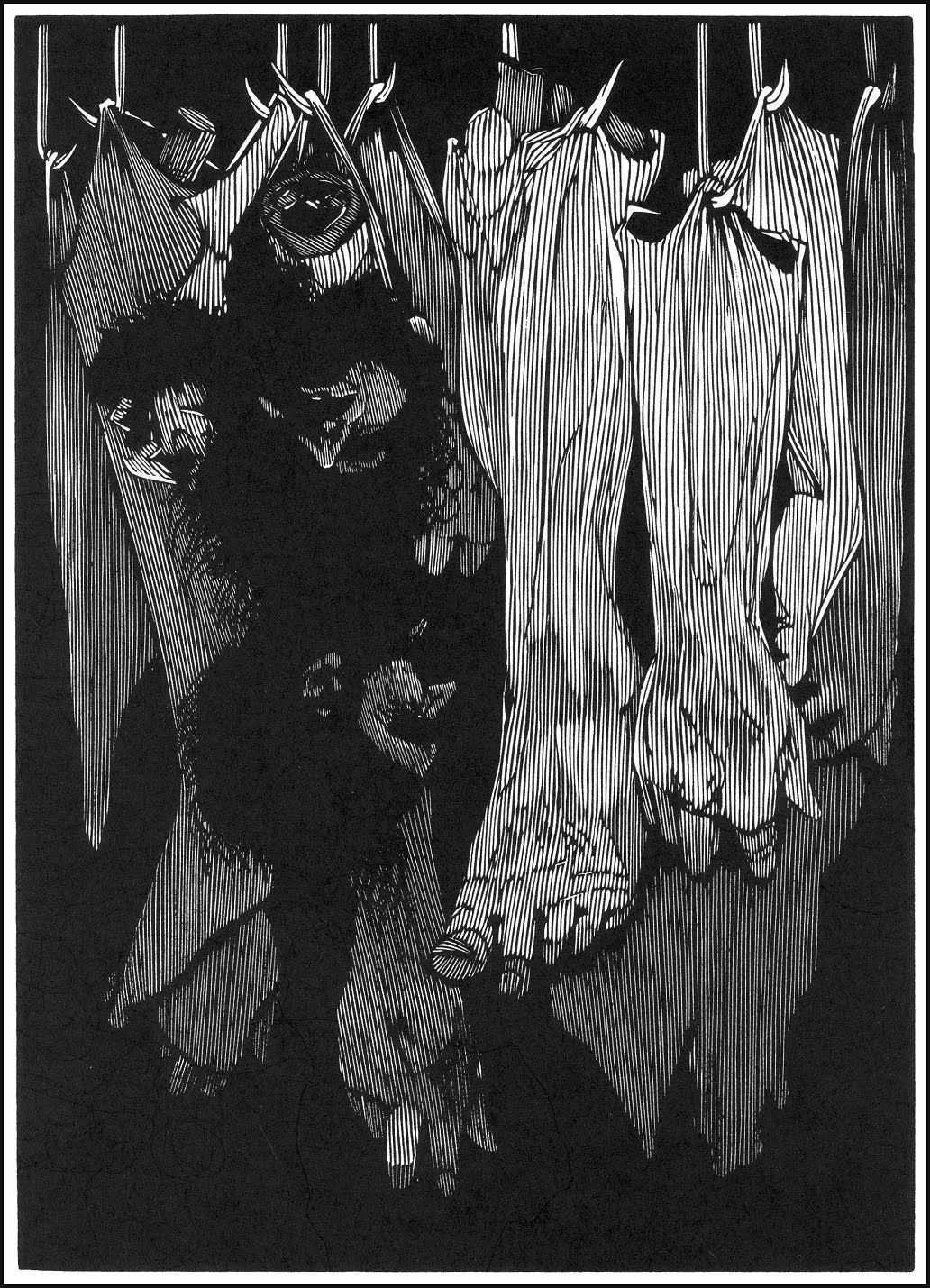

Until the passage of the Anatomy Act in 1832, which provided legal means for physicians to obtain cadavers, grave robbing by "resurrection men" was a common practice. This brutally vivid work includes firsthand accounts of the activities of the so-called "sack-em-up" men with satirical caricatures by Rowlandson, and photographs of "mortsafes," specially constructed theft-proof graves and tombs.

"I collected bones from charnel-houses and disturbed, with profane fingers, the tremendous secrets of the human frame. In a solitary chamber, or rather cell, at the top of the house, and separated from all the other apartments by a gallery and staircase, I kept my workshop of filthy creation; my eyeballs were starting from their sockets in attending to the details of my employment. The dissecting room and the slaughter-house furnished many of my materials; and often did my human nature turn with loathing from my occupation, whilst, still urged on by an eagerness which perpetually increased, I brought my work near to a conclusion."

©2018 John Martin Rare Book Room, Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, 600 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242-1098. Image: Illustration by Barry Moser from Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelly (Pennyroyal Press, 1983).