Early Modern England: Medicine, Shakespeare, and Books

Contemporaries of Shakespeare

Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), Sylva Sylvarum, or, A natural history, in ten centuries (1670)

Bacon, philosopher, statesman, essayist, and lawyer, is chiefly remembered as a philosopher and writer. He developed the inductive method of scientific investigation. Bacon rejected the deductive logic of Aristotle and believed that science should concern itself with the physical world; that its laws should be established from masses of specific data. He believed that heat is motion, identified magnetic force and gravitation, held that light travels with finite velocity, and recognized the idea of conservation of mass. In this work, he summarizes topics for investigation from works of Aristotle, Pliny, Porta, Cardano, and Sandys.

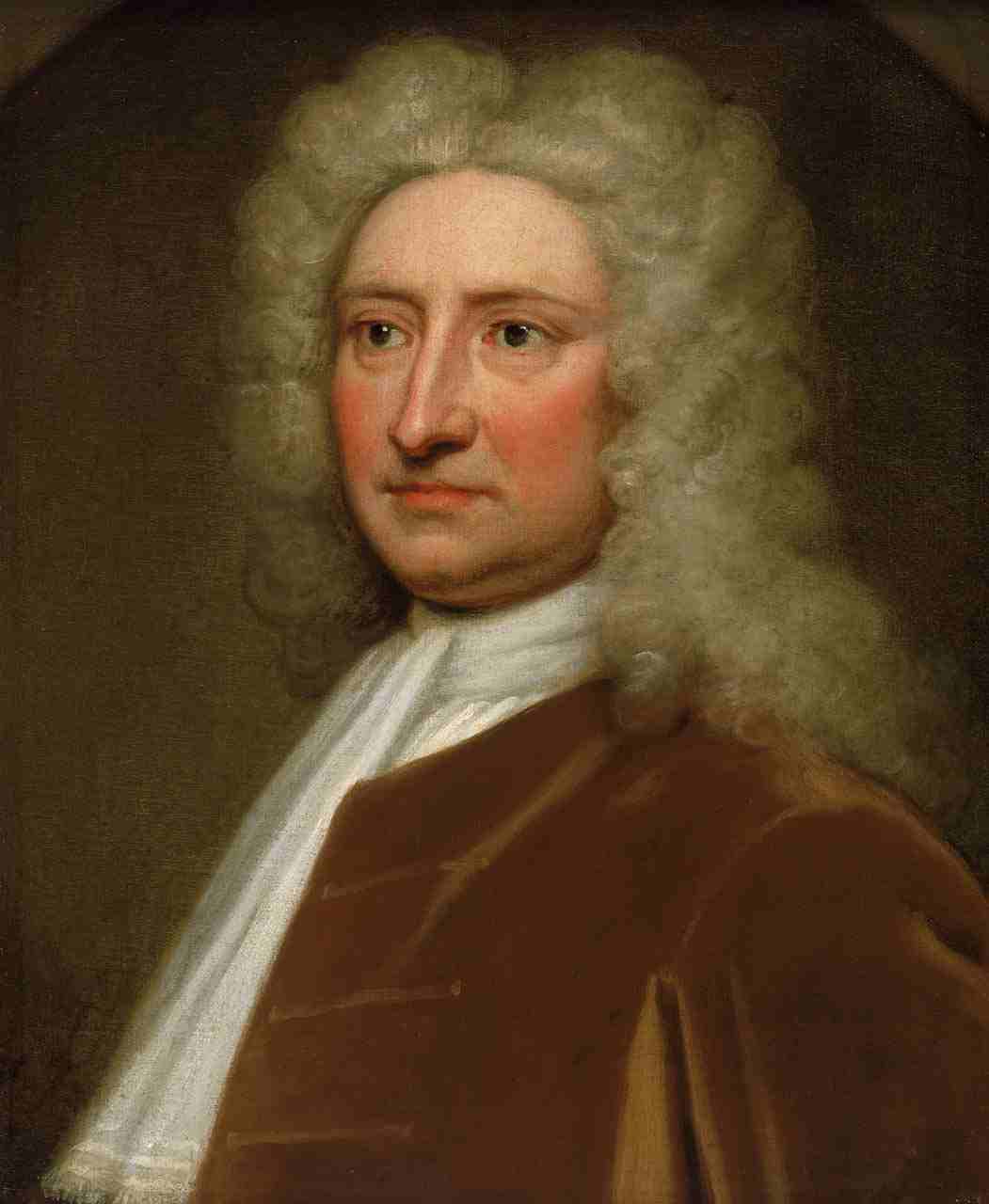

Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Certain physiological essays (1661)

Physicist, physiologist, chemist, and philosopher, Boyle was a great scientist and intellect of the 17th century. Boyle contributed to chemistry, physics, medicine, philosophy, and theology. He was a leader in the movement to separate chemistry from alchemy and was among the first to define a chemical element. His interests included studies on the properties of acids and bases, hydrostatics, respiration, combustion, magnetism, electricity, and the chemical nature of the blood. In his Essays, Boyle presents a summary of his views on physical laws and their relation to human physiology. Here he gives the first statement of his "corpuscular hypothesis," or mechanical theory of matter.

Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), A true and full coppy of that which was most imperfectly and Surreptitiously printed before under the name of Religion Medici (1643)

Browne was a noted physician and one of the great English writers and philosophers of the 17th century. In this book he sets forth his personal religious philosophy and the tenets by which he lived. His book deeply influenced many individuals and retains its appeal even after three centuries. Religio medici was so widely admired that many authors exploited the title for their own books.

Girolamo Cardano (1501-1576), La metoposcopie (1564)

Famous as a philosopher and physician, Cardano was one of the most interesting personalities of the Italian Renaissance. He wrote about philosophy, mathematics, physics, hygiene, medicine, astronomy and astrology, and theology. In this work he addresses the subject of metoposcopy, the determination of character traits as well as foretelling the future by interpretation of the lines on an individual's forehead in conjunction with their physiognomy. He recognized seven horizontal regions of the forehead, each correlated with one of the planets. Cardano includes a great number of case reports, with each he provides a frontal view of the face depicting the forehead lines and other facial marks.

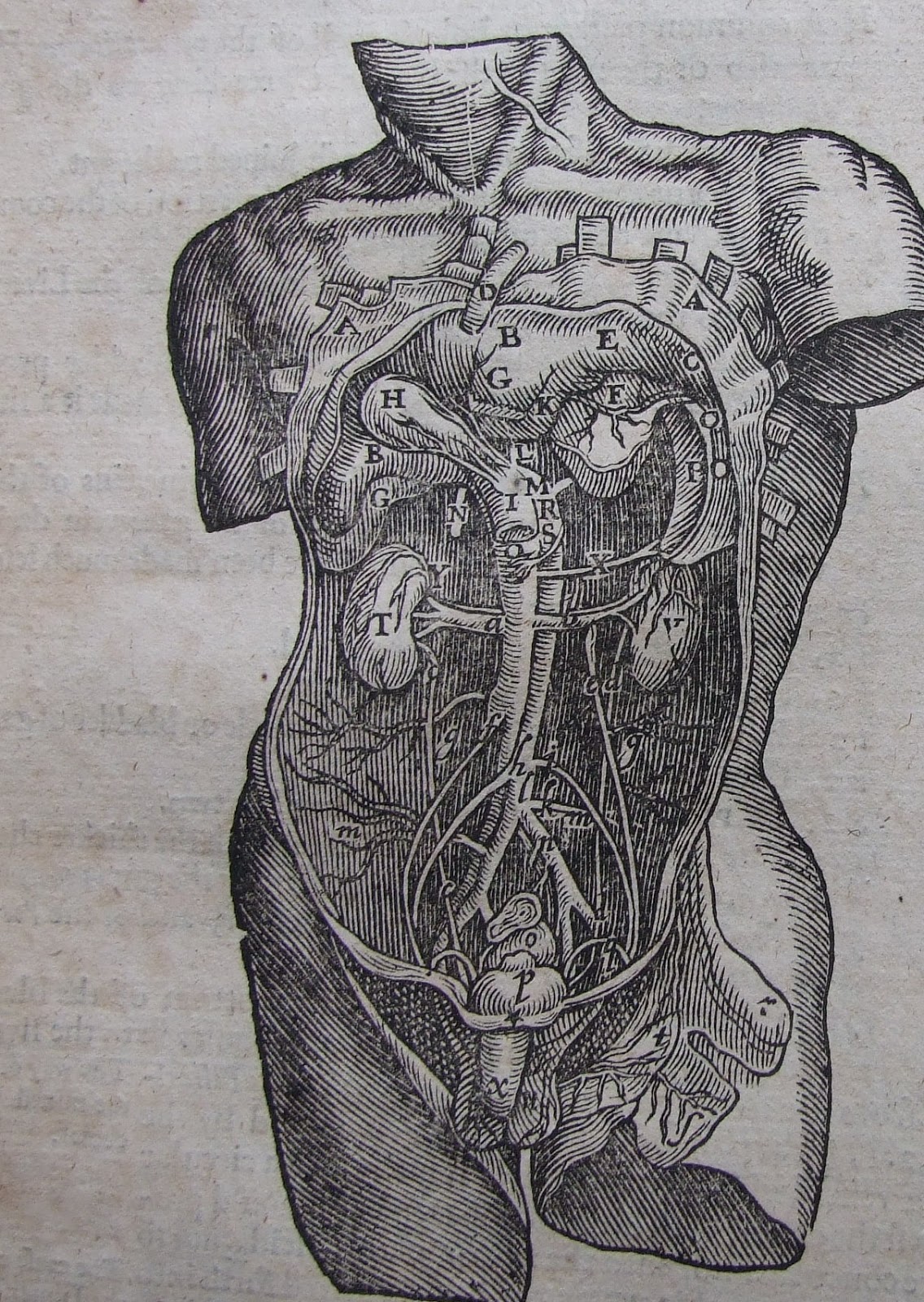

Helkiah Crooke (1576-1635) and Alexander Read (1586?-1641), Somatographia anthropine, or, a description of the body of man (1634)

Part I of Somatographia anthroponie was extracted by Alexander Read from Crooke’s Mikrokosmographia. Read, a surgeon and anatomist in 17th century, was among the dissenters to William Harvey’s doctrine that blood circulates. Crooke received his medical degree from Cambridge and was prone to be a rather quarrelsome individual of sometimes dubious character, especially when financial matters were involved. He had a number of clashes with London's College of Physicians over questions of his ethical conduct as well as the propriety of certain portions of the present work.

Sir Kenelm Digby (1603-1665), A late discourse made in a solemn assembly of nobles and learned men at Motpellier in France, touching the cure of wounds by the powder of sympathy (1664)

Sir Kenelm was a privateer, politician, traveler, linguist, scientist, and wealthy social climber. He received considerable publicity by advocating his "Powder of Sympathy." According to Digby, as a young man he was entrusted with the secret of the healing powder by a Carmelite friar who learned its preparation and use in the Orient. The powder was nothing more than vitriol (copper sulphate) which Digby claimed could heal wounds at a distance. He explained that a dressing containing the blood of the afflicted person was to be soaked in a solution of the powder, then left to dry in the sunlight. The healing properties of the vitriol and blood were transported to the wounded parts which were then healed.

Robert Hooke (1635-1703), Micrographia: or, Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses (1665)

With the possible exception of Newton, Hooke was the greatest scientist of the 17th century. His many inventions included the compound microscope, a spring for the balance of watches, a wheel barometer, the reflecting telescope, and the universal joint. This book includes studies of the crystal structure of snowflakes, experiments with light, discovery of the fifth star of Orion, and observations on the structure of hair. He discussed the possibility of manufacturing artificial fibers by a process similar to that of the silkworm and was the first to use the word "cell" to name the small pores and cavities in cork. The plates depict a wide variety of plants, seeds, moss, insects, cross sections of wood, cork, hair, and gravel from the human bladder.

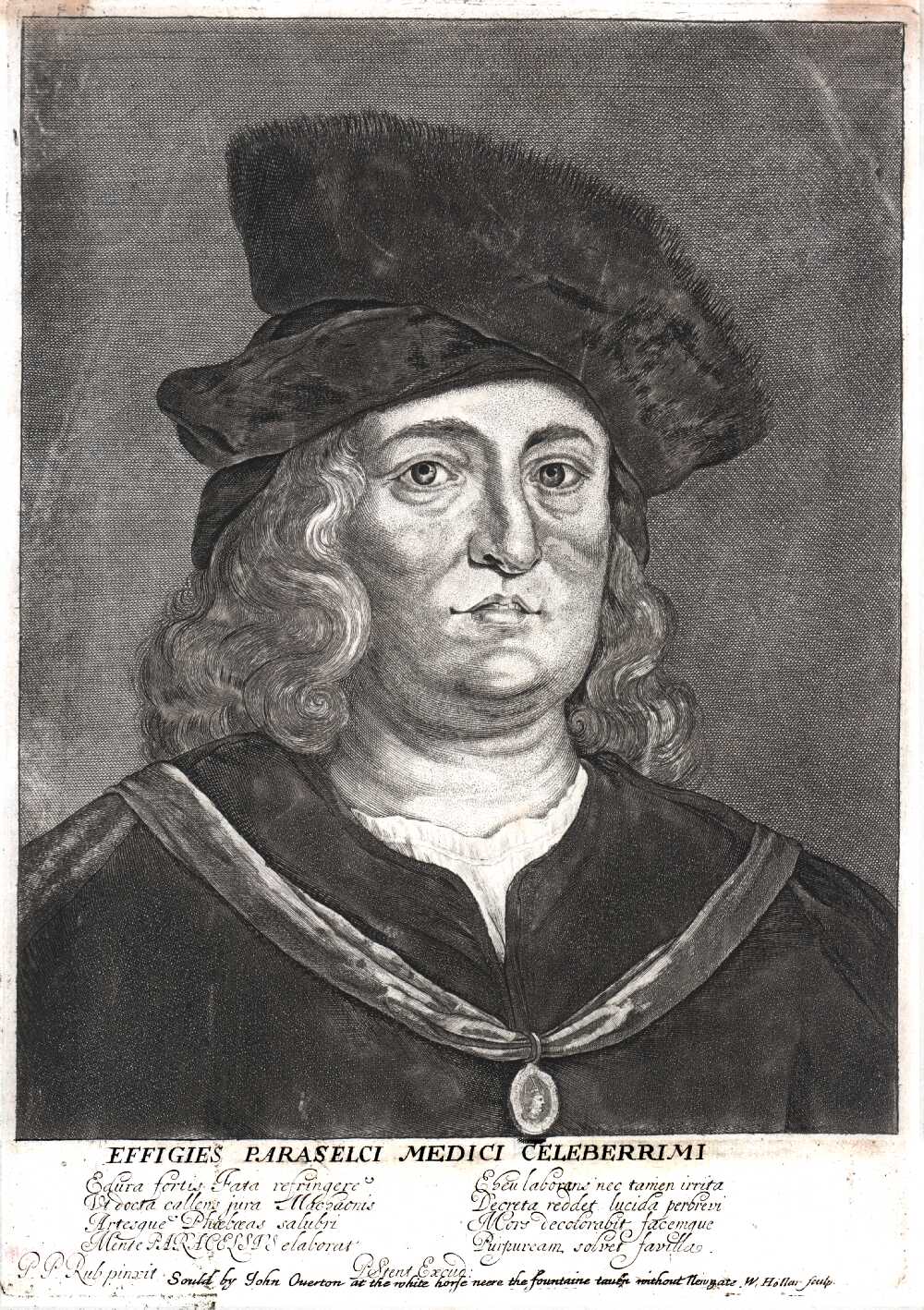

Paracelsus (1493-1541), Astronomica et Astrologica (1567)

Philippus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim is universally known as Paracelsus. His unorthodox ideas and teachings put him at loggerheads with the orthodox establishment of his time and he spent most of his life wandering through Europe as an itinerant physician, chemist, theologian, and philosopher. He applied chemical techniques to pharmacy and therapeutics, and in his medical teaching he abandoned the system of humours. References to the stars are found throughout his writings. He based his astrology on the theory of the interaction of man (microcosm) with the universe (macrocosm). He considered astral influences to be one of the five causes of disease including poisonous and impure substances, psychological, spiritual, and divine causes.

©2017 John Martin Rare Book Room, Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, 600 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242-1098

Image: Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia (detail), 1851-52, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 111.8 cm, Tate Gallery, London.