Early Modern England: Medicine, Shakespeare, and Books

Poisons and Cures

—Cornelius, Cymbeline, Act I, Scene 5

Avenzoar (d. 1162), Abhomeron Abynzohar. Colliget Averroys (1514)

Avenzoar was a great physician of the Cordovan or Western Caliphate and was staunchly opposed to astrology and mysticism in medicine. He favored a rational approach to medicine with emphasis on practical experience. The Abhomeron or, Theisir ("The alleviation of disease") is his chief medical work. In this treatise Avenzoar describes methods of preparing medicines and diets and gives sound clinical descriptions of the itch mite of scabies, paralysis of the pharynx, serous pericarditis, and mediastinal abscess. He practiced surgery to a limited degree. The companion work, Colliget, is a translation of a work by Averroës, a contemporary of Avenzoar who may have learned medicine from him. It is a medical treatise and an attempt to establish a system of medicine based on Aristotle’s philosophy.

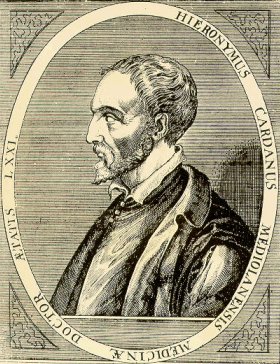

Girolamo Cardano (1501-1576), In septem Aphorismorum Hippocratis particulas commentaria; De venenorum differentiis, viribus, & adversus ea remediorum praesidiis; De providential temporum liber (1564)

The present work contains a translation into Latin of the Aphorisms of Hippocrates with Cardano's extensive commentaries and a treatise on poisons and their antidotes. Giovanni Battista, Cardano's eldest son, was tried and beheaded in 1560 for poisoning his wife.

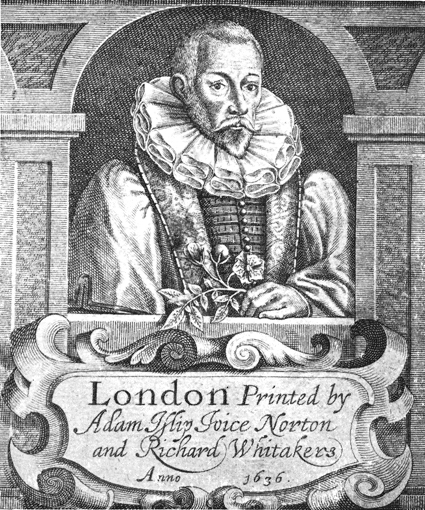

John Gerard (1545-1612), The herbal or Generall historie of plantes (1633)

Gerard was a botanist and herbalist. The botanical genus Gerardia is named in his honour, and he maintained a large herbal garden in London, but is best known as the author of a large (1,484 pages) illustrated Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes. First published in 1597, it was the most widely circulated botany book in English in the 17th century. Gerard's Herball is profusely illustrated with high-quality drawings of plants, with the printer's woodcuts for the drawings largely coming from Continental European sources, but also containing an original title page with copperplate engraving by William Rogers.

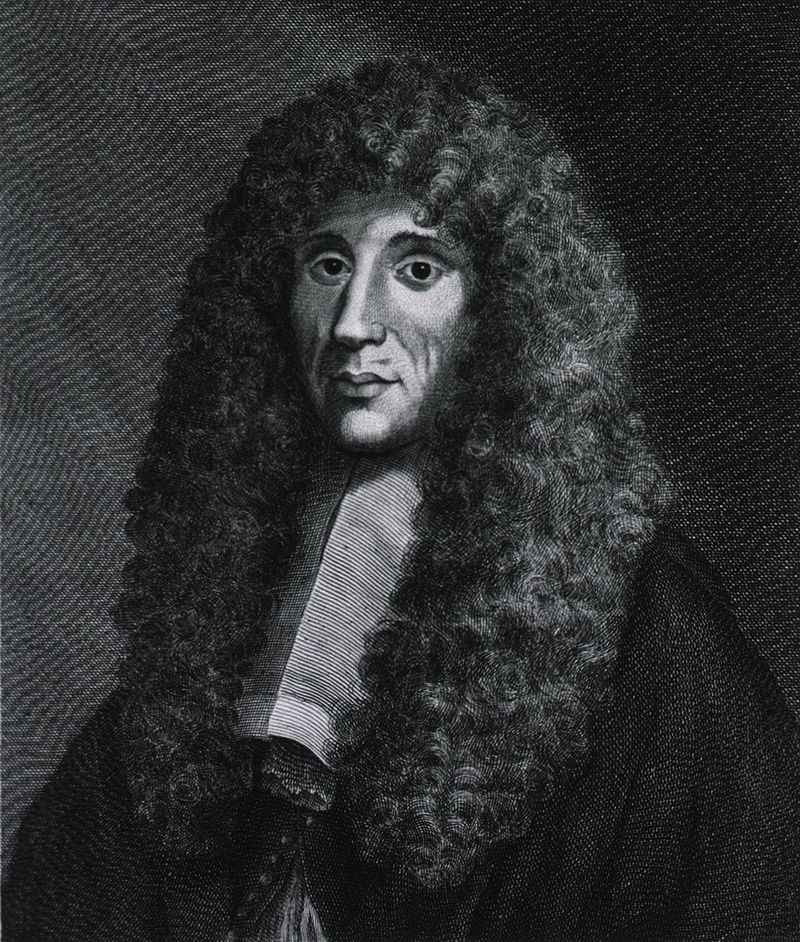

Francesco Redi (1626-1698), Osservazioni intorno alle vipere (1664)

Redi has been called the father of helminthology, and wrote one of the earliest works on parasitology. Redi described more than 100 species of parasites and was an avid student of the development of snakes, birds, insects, and fish. The present work on the poison of vipers, as well as that on the generation of lower animals, places him at the forefront of the biologists of his time. In this treatise, Redi described his experiments with various poisonous snakes. He demonstrated that when the venom is mixed with food and ingested into the stomach it is harmless. In additional experiments he showed that venom has no effect if placed on the surface of the skin but must be introduced into the circulatory system in order to be effective.

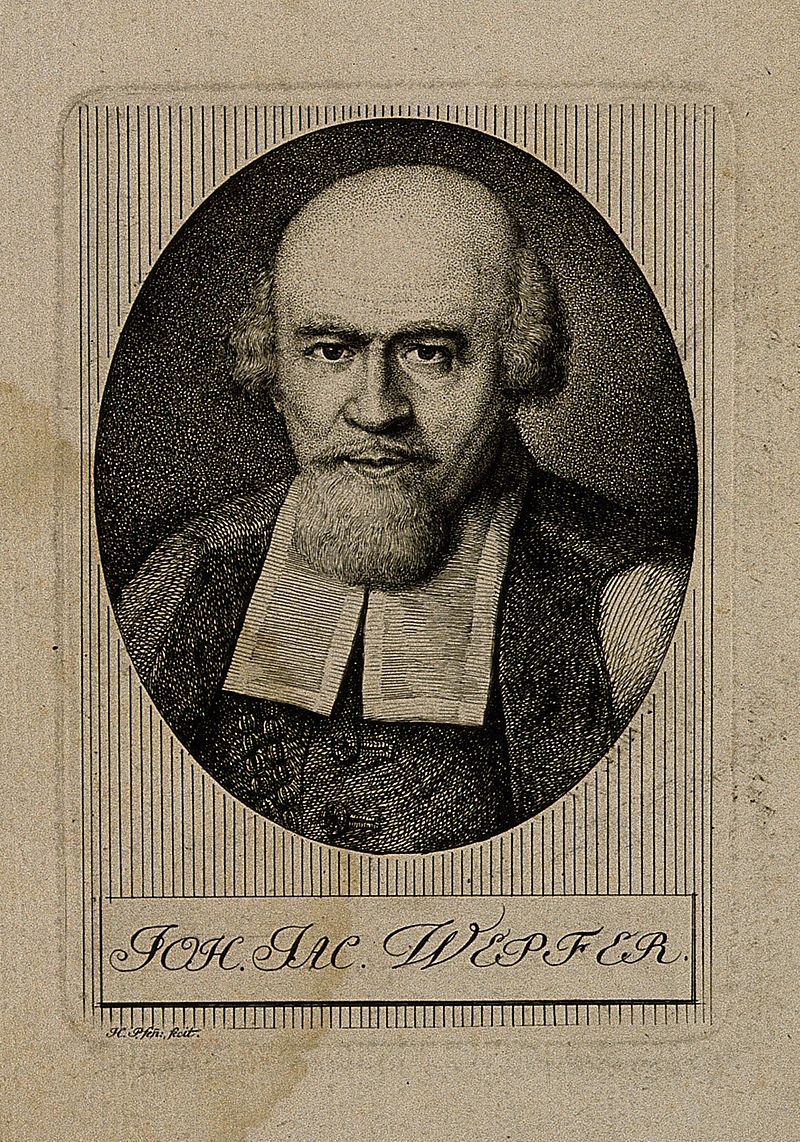

Johann Wepfer (1620-1695), Cicutae aquaticae historia et noxae: commentario illustrate (1679)

This is primarily a work on the poisonous water hemlock, discussing its dangerous effects, its medicinal uses and antidotes to counter the poison. Four engraved plates illustrate one species of the hemlock family, the roots and lower stalk, the branching stalks, the leaves and the flowers and seeds. Wepfer systematically studied poisons, with particular attention to the toxic water hemlocks. He was the first to analyze the pharmacological effects of coniine, an alkaloid of hemlock that was not isolated until much later; and his classic description of hemlock poisoning was often cited as the standard. Parts of the book contain letters or extracts of letters between Wepfer and other toxicologists of that era.

Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane—from the genus aconitum, and also sometimes known as monkshood—has been recognized as a poison since ancient times. Its roots contain large amounts of pseudaconitine, an alkaloid which is deadly to humans. Shakespeare refers to it in Henry IV Part II, calling it as strong as “the venom of suggestion.” In modern popular culture, wolfsbane is employed as everything from a protection against vampires (Bram Stoker’s Dracula), to a potion to delay the affects of lycanthropy (the Harry Potter series).

©2017 John Martin Rare Book Room, Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, 600 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242-1098

Image: Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia (detail), 1851-52, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 111.8 cm, Tate Gallery, London.